A castle on a swamp: part 1, competitive games

Pokemon is a big deal.

Pokemon playing cards. Pokemon video games. Pokemon manga. Pokemon toys, and Pokemon TV shows, and Pokemon movies, and Pokemon plushies. Pokemon is the biggest media franchise of all time, surpassing Star Wars and Harry Potter and Mickey Mouse and Winnie the Pooh.

Pokemon is a big deal.

Pokemon is such a big deal that it even has an active competitive scene. Yes, that means people who devise strategies and think tactically while playing what was originally a kids game. A lot of people. And, as it turns out, there’s something really interesting in the way they play.

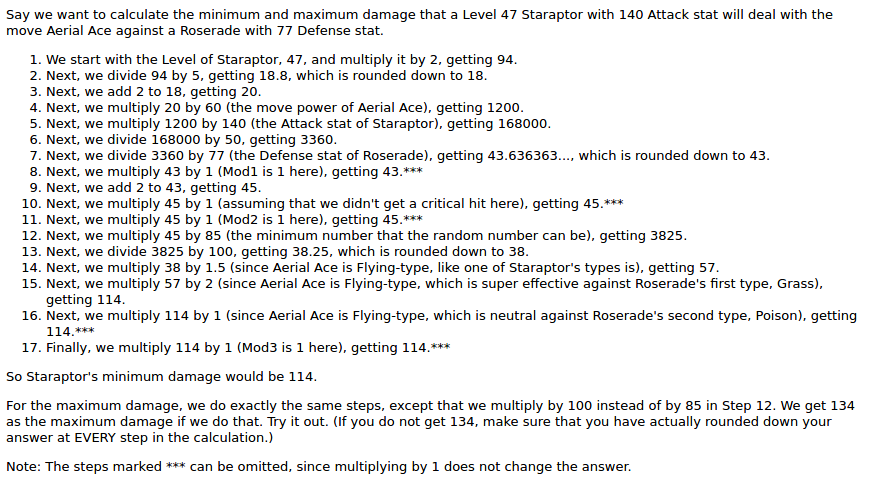

One thing I’ve learned about the internet is that you can always find a group of hardcore nerds who have gone above and truly beyond in their quest to master their art. For competitive ‘mons, we have folks who have organized world championships and built a full-fledged game simulator and even deciphered the assembly code to reverse engineer how the game works.

You know you’ve gone down the rabbit hole when your research into a so-called “kid’s game” looks like a mathematical ritual to summon Cthulu

Here’s where things get interesting: not only has the competitive Pokemon community stretched the basic game mechanics to its absolute limits, it’s also put a serious effort into making the game competitive to begin with.

Competitive games are defined by one key feature: the better player should usually win. Pokemon, in its default state, is incredibly uncompetitive. There are strategies that can easily reduce the game to almost pure chance or even force the game to go on, quite literally, forever.

Pokemon is unlike many of the games we’re used to playing. There’s no luck in chess so you can’t blame external factors for the game outcome. There’s chance and luck in poker, but skilled players can manage it so well that, in the long run, they reliably come out on top versus noobs. In football, the playing field might not be perfectly equal because the people you play with have different heights, weights, levels of physical fitness, and so on, but you can usually still cobble together a decent match if you try.

In comparison, Pokemon is about as competitively viable as football played on a field with an area of fifty square kilometers, with twelve balls, and a hundred and fifteen players a side (but over the course of the match, ninety-six players will be turned into squirrels at random). Oh, and hungry hippopotamuses roam the field, ready to bite you and drag you into a lake if you look at them the wrong way. Theoretically, both teams have an equal chance of victory because the teams start off exactly the same (it’s not like one side has more players or anything), but a competitive game? Absolutely not.

Somehow, despite all the “cheese” strategies and overpowered abilities and critical hits and coinflips built into the game, the miracle is that a small group of dedicated weirdos managed to agree on a compact, coherent set of rules and actually establish a stable philosophy of how to make the game playable. They’ve created a reasonably competitive game while adhering closely to the way the original games work. Out of chaos they’ve created order. It’s like they tried to build a castle upon a swamp, except it actually worked.

“Everyone said I was daft to build a castle on a swamp, but I built it all the same, just to show them. It sank into the swamp. So I built a second one. And that one sank into the swamp. So I built a third. That burned down, fell over, and then sank into the swamp. But the fourth one stayed up.” -Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Interestingly, there have also been multiple attempts at creating a competitive Pokemon community in the past and most of them have faded too, but eventually things stabilized into an actually playable game. Draw whatever parallels you want.

The hard part about making good competitive games is that it has to be stable enough to be playable, but allow for enough complexity to make it interesting. Chess works as a competitive game because there isn’t a magic chess piece that can capture half the other pieces in a single move. Soccer works as a competitive game because goals are scored one at a time; there’s no such thing as scoring a hundred and fifty goals in a minute. Things don’t magically blow up in the last minute and make your earlier efforts all game meaningless. Your opponent can’t reduce the game to a 50-50 coinflip. These games are fundamentally stable.

But even within the confines of their rules, we can have many different strategies. For most competitive games that have stood the test of time, the stability comes from the relatively simple ground rules and the cool strategies comes from the complicated scenarios that then emerge.

That’s what makes competitive Pokemon different. The basic mechanics are already complicated and already allow for completely unplayable situation. The competitive fanbase made things stable by reducing what you can do and banning things, rather than building complex strategies on top of a simple rule set. They went the other way.

The really weird thing I’m starting to notice is that a lot of things we take for granted are more like Pokemon than other games. We normally think the foundations are stable and we build cool things on top of that, but in a lot of cases the opposite is true.

Most of the time, we don’t see the instability because what we’ve built is really good at maintaining the illusion of reliability. We don’t notice the shaky ground. For many parts of our world, competitive Pokemon is closer to reality than soccer is.

Once I started noticing it, I started to see it everywhere. And pretty soon, you will too.