Vaccinate NJ

Vaccinate NJ was a volunteer-led project to solve the COVID-19 vaccine availability information problem in New Jersey.

At the start of the vaccine rollout, it was hard to navigate the confusing patchwork of medical systems to get vaccinated. We had an information bottleneck problem that our existing infrastructure did not solve. As a result, I created and led Vaccinate NJ. This is its story.

The early days

On December 14, 2020, Sandra Lindsay became the first person in the United States to get a COVID-19 vaccine after it was officially approved by the FDA. This kicked off the nationwide vaccine rollout. If you were eligible, you could sign up for an appointment and get vaccinated against COVID-19. At least in theory. As it turns out, it was substantially more difficult than it might’ve seemed at first glance.

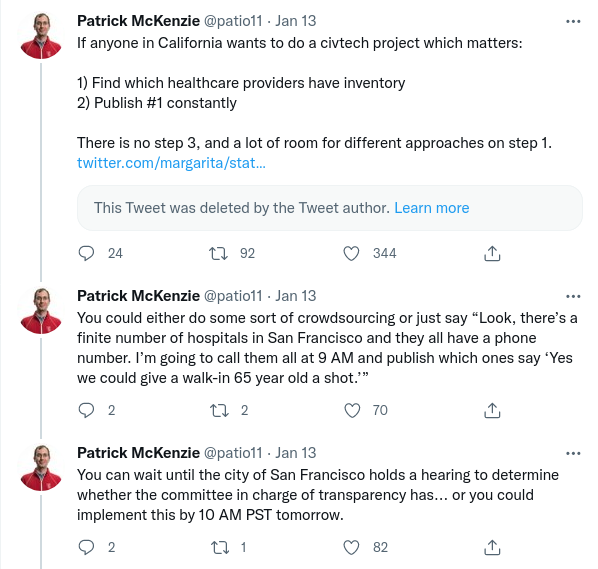

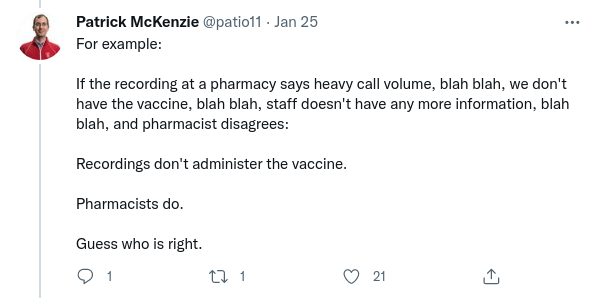

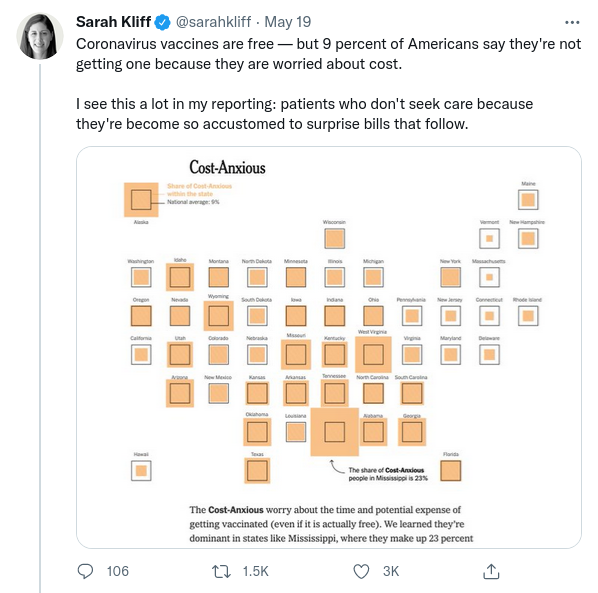

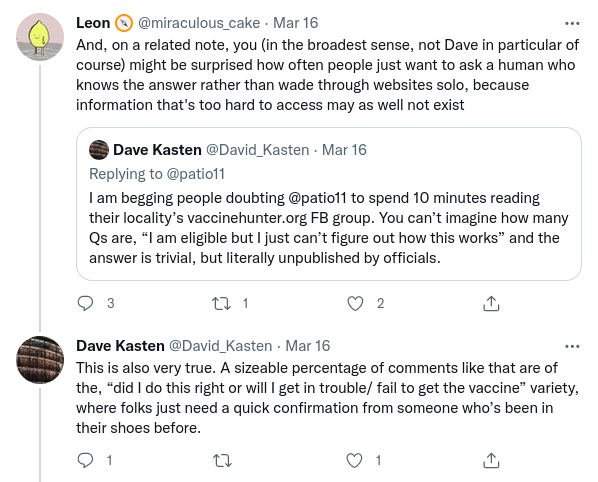

Early in 2021, I came across this series of tweets:

Inspired by this thread and by how quickly people on the internet started working on this for California, I decided to start working on this same project for New Jersey shortly afterwards. What ensued in the following days, weeks, and months became known as Vaccinate NJ.

The eligibility question

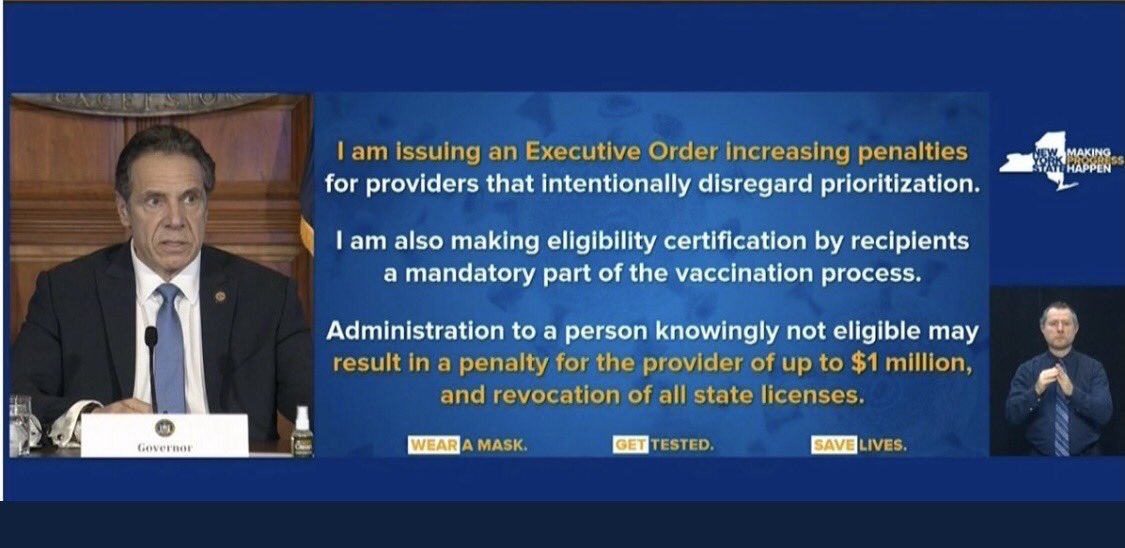

My first goal with Vaccinate NJ was to solve the problem of keeping track of eligibility rules. Like in many other states, New Jersey had a set of eligibility requirements for receiving the vaccine at the start of the rollout. These rules, in principle, were meant to prioritize doses for high-risk groups first, such as the elderly and those with weakened immune systems1. However, several factors led to confusion amongst those looking for a vaccine:

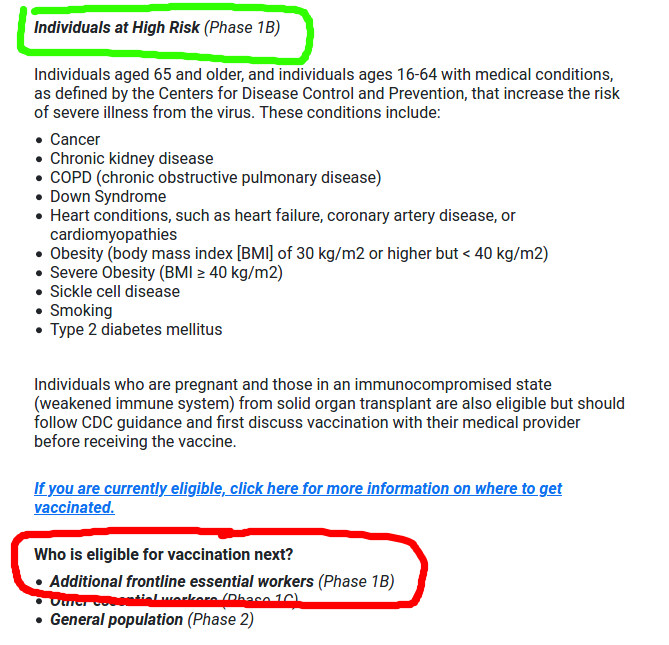

- Eligibility rules changed frequently in subtle, easy-to-confuse ways. For instance, the eligibility rules initially divided New Jerseyans into four categories: 1A, 1B, 1C, and 2. However, it soon became easy to get confused trying to navigate the frequently-changing rules.

This is a screenshot of the official eligibility guidelines website on January 14, 2021. Notice that some people in phase 1B are eligible and others are not, despite both being in phase 1B.

-

New Jersey implemented an online “pre-registration” system, which collected various personal information to provide vaccine information updates. This was subtly but importantly different from actually signing up for a vaccine appointment, and this confusion frequently appeared in questions written on social media, message boards, and other places people asked questions about the vaccine rollout.

-

Eligibility rules listed on the state website did not guarantee being eligible for a vaccine at a specific site. For example, someone might be over age 65 but still not be allowed to receive a vaccine at a particular hospital if that hospital decided to give doses only to medical workers (a decision which was the hospital’s to make, not the government’s, given the decentralized nature of the vaccine rollout). This information was not always immediately clear to vaccine-seekers.

Over the course of the vaccine rollout, I maintained an up-to-date questionnaire on the Vaccinate NJ website with questions in plain English to help clear up confusion around eligibility.

Force multipliers

After getting a basic website up and running in a night or two, I faced two main problems. The first was that Vaccinate NJ started as just another small voice amidst the shouting contest that is the internet, and it wouldn’t be of any use to anyone if they didn’t know about the website to begin with. The second, I soon discovered, was that eligibility alone wasn’t enough for getting an appointment. Vaccine availability changed fast, for all sorts of reasons: everything from fluctuations in vaccine shipments to appointment system changes all the way to winter snowstorms shutting down highways and vaccination centers.

This was a problem. I was just one person, sitting alone at the desk in my bedroom. On my own, there was a very serious limit to how much I could do and how impactful this project could be. For Vaccinate NJ to actually solve the problems it set out to solve, I’d need force multipliers.

Get the word out

Outreach was an especially tricky challenge in the early days. I didn’t have a large platform with which to get the word out. I wasn’t deeply embedded in many of the complex communications networks crisscrossing our communities, transmitting information at the speed of word-of-mouth. I didn’t have connections to centralized media organizations, nor did I know much about decentralized groups such as the various groups on social media that emerged organically during the pandemic. After exhausting the obvious approach of telling everyone in my immediate social network and asking them to pass it on, I needed to find another way forward, no matter if it was unconventional.

It was difficult at first. At one point, I made a list of various journalists for every single county in New Jersey, calling and emailing them all to see if local media would be willing to accept this story about a home-grown project of significant public interest. No one seemed to be particularly interested in the stories about the vaccine rollout at the time, despite the ongoing pandemic. Just one person expressed interest, but he only wrote about sports so he agreed to run the idea by his boss– no promises though.

In the meantime, I scoured the internet in case other people were working on similar projects. At first, my searches turned up nothing. It seemed like everyone had just resigned themselves to living in a world where vaccine websites broke, phone calls went to robotic answering machine systems, and information bottlenecks were just a way of life.

But then the dominoes started to fall. The day I wrote my first tweet looking for volunteers, I started receiving messages from people who were interested in helping out. I found a local journalist who’d started working on a similar, albeit more localized project, which led to press coverage (see: exhibits A, B, C, and D), which led to massive increases in our audience, which meant we could actually make a big difference.

Within two days we had a list of a hundred vaccination sites. A day after that, our list had up-to-date information on every vaccination site listed on the official website as well as status reports on others that hadn’t even been officially announced yet. A week after that, we had a hundred volunteers who signed up to gather vaccine availability data and help with further outreach. I– or, at this point, we– had the force multipliers we needed.

Now it was time to deliver on what we’d promised.

The data problem

Finding an appointment in the early days was a frustrating process. It was all too common for people to have to call many vaccination sites and check many websites over the course of days, weeks, and months to find an open appointment slot. I still remember the story that one elderly, high-risk couple told me about sometimes waking up at 5 AM and sometimes staying up past midnight, just in case new appointments suddenly appeared at odd hours (which, as it turns out, they sometimes did). Others simply lacked the free time to stay glued to their phones and computers, so they just gave up searching for the time being. Others still had concerns about the logistics of getting a vaccine and reluctantly decided to accept the risk of delaying things2. Many times, the best source of appointments came not from any official source but rather from unofficial discussion groups on social media and internet message boards.

There were many factors that contributed to this difficulty in getting an appointment. We were well-positioned to help specifically with the challenge of staying up-to-date on appointment availability information, so we focused on that. The decentralized vaccine rollout meant the New Jersey state government knew where the vaccines were being physically shipped, but not the specific plan for administering them. That decision was left up to medical professionals or administrators at the vaccination site to decide. Though there was an official website tracking all vaccination locations in the state, the website initially was only updated about once every two weeks and didn’t say which sites had open appointments (or, for that matter, which of the sites were even operating at all).

Meanwhile on the vaccine provider end, publishing information was also a challenge. Decentralizing the vaccine rollout also meant decentralizing the spread of information. There was no single centralized appointment scheduler for the state as a whole. Instead, each county, pharmacy, medical institution, or other type of vaccination site had to build their own separate appointment management system, each one of which might’ve operated differently from the others.

One might have hoped that the data problem boiled down to writing a bunch of web scrapers and setting them loose on the internet. Unfortunately, at the start of the vaccine rollout, this alone wouldn’t have worked. There were cases of websites crashing under heavy load, producing cryptic error messages, having outdated information, or requiring users to complete a lengthy form before informing them that there was no availability to begin with.

Getting the right answer

I’m a software person at heart. I like to think in terms of automation. In an ideal world, setting up a beautifully-architected system with automated bots everywhere would have been great for getting the ground truth about appointment availability, and getting it fast. Unfortunately, the real world is rough around the edges, and it’s the edge case that tends to make automation fail the most. In fact, the real world is mostly edges– especially in this situation, which often changed faster than the status websites were manually updated.

This might look like a rather demoralizing state of affairs, but there was a way out of the conundrum: talking to actual people. The person best positioned to know the ground truth was the medical worker on the ground who was actually administering the vaccines. For each vaccination site, we wanted to reach them (or the person at the front desk nearest to the phone, but importantly a professional on-site either way) rather than a website which may or may not have been several weeks out of date. And that’s precisely what our volunteers started off doing.

There’s a saying that goes something along the lines of, “If you see two signs that contradict each other, trust the one that looks like it was posted more hastily.”

Vaccinate NJ, by acting as a centralized, constantly updated, accurate display of information, worked to solve the information problem on both ends. Appointment-seekers only needed to check one website instead of many, saving them time and energy. The website also substantially reduced the load on healthcare providers’ communication systems. One phone call from us counted for many phone calls from every single person who would’ve otherwise needed to make their own call. All that extra traffic would be redirected to Vaccinate NJ’s website instead. As it turns out, it’s a lot easier to scale up a web server than it is to scale up medical professionals’ valuable time.

Software steps up

Many of the technical decisions from the early days made sense in the short-term, buying valuable time and helping Vaccinate NJ get off the ground. We violated basically every single piece of popular wisdom in software engineering about technical debt and scalability, trading off “good engineering principles” for short-term speed when it mattered most. It’s not every day that you get to decide the database of choice is the humble spreadsheet, or that human-in-the-loop is the hammer for every nail.

But this wasn’t sustainable over the long run. Several weeks into the start of the project, the crisis certainly hadn’t ended but it was starting to become clear that we couldn’t run on the fumes of new-project energy forever. It was time to regroup and build the tools necessary to keep things from slowing down. This is when software stepped up.

In the early days of Vaccinate NJ, it helped a surprising amount to have a domain name, a custom logo, and a clean user interface. The goal was to signal that the Vaccinate NJ website was a serious project built by professional software engineers, not something hacked together last-minute in a time of crisis. (Of course, the reality is that the Vaccinate NJ website was a serious project built by professional software engineers hacking things together last-minute in a time of crisis, but I found that it went a long way just to focus on the first half when we needed to signal our legitimacy as an organization.) The short, memorable URL was also easier to share with vaccine-seekers and journalists alike, than the shared spreadsheet’s lengthy URL.

Before long, however, we started running into technical challenges with the spreadsheet, such as running into limits on the number of people who could view the spreadsheet at a time. Data integrity also became a challenge as the list of vaccination sites expanded more and more and it was easy for typos and mistakes to creep in. Tricky decisions emerged as we encountered the edge cases that reality is made of, such as “if we’re organizing the list of vaccination sites by county, how do we represent a hospital which has branches in multiple counties, all of which use a shared vaccine appointment system whose user interface might change at any time?” Ignoring these problems made sense at a small scale, but now it was time to make Vaccinate NJ easier to use as well as update and maintain.

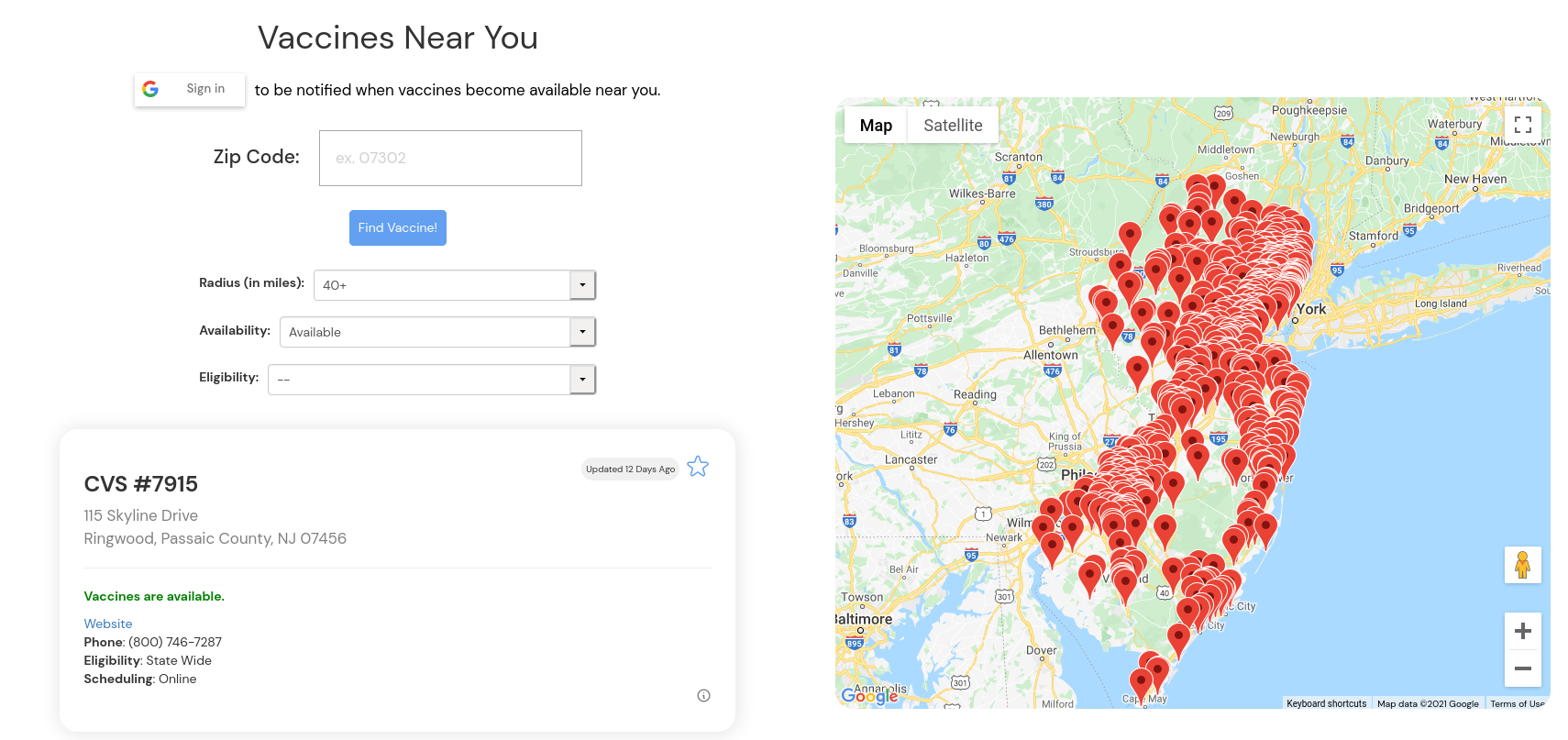

Fortunately, by this point Vaccinate NJ was far, far from a single-person operation. Our volunteers did an incredible amount of work from a technical aspect (in addition to their outreach and information-gathering operations). Some identified certain types of vaccination sites whose websites had actually caught up to ground truth, allowing us to make use of web scrapers that would’ve previously been unreliable. Others helped turn the spreadsheet into a database with built-in data validation, making data entry substantially easier. That database became the backend for a searchable, user-friendly map interface that not only updated its availability information in real time but also allowed people to sign up for alerts when new appointment availability was confirmed. At peak we had tens of thousands of website visitors a month, and our Twitter account peaked at over thirty thousand followers. It’s honestly hard to overstate how crucial their contributions were to making the project work.

Looking back

Building Vaccinate NJ was an effort like none other that I’ve taken on in my life. I learned quite a bit about how rapidly-growing, fast-paced projects work, and about the power of software. I learned from the challenges at every scale, from getting started on my own to working with the enormous, interconnected systems that make our world tick, and everything in between. My hope is that these lessons will be of use to those in positions like mine in the future.

Own it

If there’s one thing to take away from Vaccinate New Jersey, it’s the effectiveness of taking ownership.

Vaccinate NJ didn’t rely on having access to secret information or resources that ordinary citizens lacked access to. Our secret to success is that we identified a problem and decided “we own this problem, now”– in other words, choosing to be the ones responsible for making things in this particular domain work, and work well.

Large, complex systems can produce undesired outcomes even if no one is intentionally trying to ruin things. Sometimes vital system components break and stay broken simply because it wasn’t anyone’s job to make sure that part was working as intended. The vaccine rollout has many parts, from vaccine manufacturing to logistics and distribution to dosage inventory management to appointment systems to the user-facing web and phone interfaces. Our goal, as Vaccinate NJ, was to own the appointment and eligibility information component as best as we could.

To be sure, ownership certainly isn’t trivial. Sometimes it’s difficult just to notice that a critical but non-obvious part of a system has no owner. Choosing to take ownership is a weighty decision that isn’t easy to undo. At the same time, opportunities to wield ownership are surprisingly abundant and surprisingly accessible. We might be told, implicitly or explicitly, that helplessness is the default, but it is by no means our only option. There’s power in picking a fight and making it our own.

Designing for the user

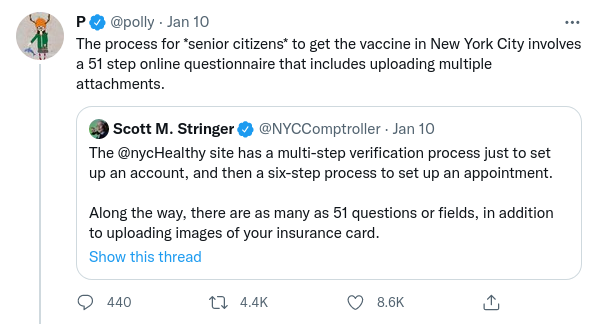

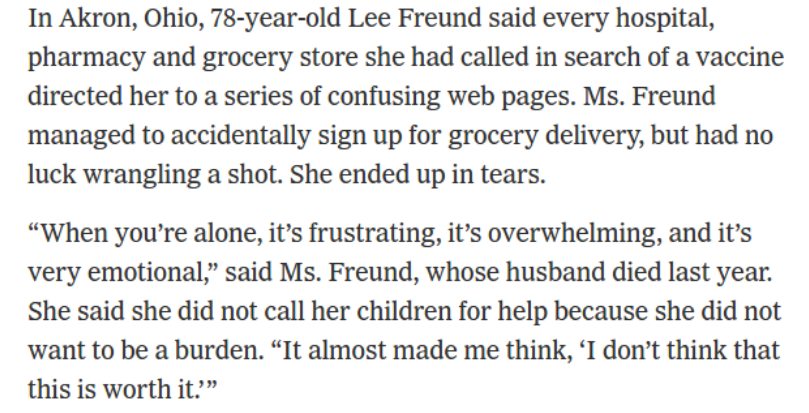

If you’re reading this, there’s a good chance you own a computer and can use it without too much difficulty. I myself write software for a living. For people like us, seeing an error message written in all-red text or dealing with difficulties when filling out a form online isn’t too intimidating. It’s easy for us and those like us to forget that this isn’t a universal skillset and website design does actually make a meaningful difference in how vaccine-seekers go about looking for appointments.

From the New York Times. To paraphrase Paul Graham here: being comfortable with computers means having a reassuring voice in your head saying “if I can’t figure out, it’s not my fault; the software’s just poorly designed.” People who aren’t computer-savvy often have a voice telling them they’re stupid.

One idea I’d heard many times before (albeit in a very different context) is “if you can’t easily find and understand the data, you might as well not have it.” This was particularly true for vaccine hunting– if people can’t find available appointments easily, then it’s no good to have doses sitting in a freezer at the actual vaccination sites. Our work didn’t depend on a revolutionary approach to software, but instead a combination of outreach and easy-to-access, easy-to-understand information.

Something beats nothing, always

Once the gears started turning, one of the principles that kept coming up was “something beats nothing, always.” Keeping this at top of mind was, at least for me, absolutely critical to sustaining morale. I am not a logistics or public health communications professional. The core user-facing part of Vaccinate NJ was a website, but many of our hard-working volunteers weren’t programmers. And despite all of this, Vaccinate NJ still took off and everyone’s efforts made a major difference.

Sometimes it could seem demoralizing, making calls to vaccination sites and finding out they’d booked all their appointments between February and August with no availability in-between. On the contrary, it was important to remember that a “no” was still useful information because it let us prioritize checking on vaccination sites that were more likely to have doses. It also meant saving vaccine-seekers a phone call since a “no” is a clear, useful answer to their question as opposed to “I don’t know”.

In a similar vein, we moved quickly to make sure the overall project could still move along even if no one individual person could devote time to it every single day. Life is filled with unexpected events and people aren’t machines, so we had to make sure volunteers could contribute even if they couldn’t make massive commitments to the project. We wanted to make sure every phone call and every bit of outreach mattered, and it did. Something beats nothing, always.

This principle was relevant even on easily-overlooked topics like having a distinctive, professional-looking logo. We used our logo everywhere, including on our website and on social media. A logo, like having an official website, gave us more legitimacy and trust than just an isolated internet spreadsheet would’ve. This went a long way towards letting us have as large an impact as possible. One might dismiss the logo as being trivial, but compare it to the alternative of having no symbol at all. Would you trust a project whose profile picture on social media is the gray, anonymous default?

A side-by-side comparison. Incidentally, our logo was created by a high school student. I frequently encounter the attitude that children are merely adults-in-training and therefore unable to contribute anything meaningful to projects outside of the context of school. I’ll let history be the judge of that.

The power of compounding

Humans need to sleep. Viruses don’t.

Right from the beginning, we were racing against an adversary who doesn’t get tired or demoralized, slow down, get delayed by snowstorms, or recognize weekends and holidays. Human timescales and viral timescales are simply too different for us to fight the pandemic head-on. If we, humanity, had tried to go eye-for-an-eye with the virus, we’d have lost.

Luckily, we humans have a few tricks up our sleeve, like the ability to coordinate our efforts, and the ability to share knowledge, and the ability to build things that compound. Our vaccines against their spike proteins, our for-loops against their exponential spread. In a fight against a relentless opponent, our greatest asset is being able to create systems that work while we sleep.

If I had to do Vaccinate NJ all over again, I’d take this principle more seriously right from the very beginning of the project. In the early days, I remember thinking that I’d stay up just a little bit later to get one more little thing done, in the name of racing the pandemic clock. If one lost hour of sleep meant making a substantial amount of progress towards getting life-saving vaccines to people who needed them, well, I was willing to make that trade. (This isn’t a comment on the general concept of work-life balance, by the way– just a choice that I made of my own accord, specifically for myself, specifically for this situation.)

The problem with staying up late is that it works right up until the point that it doesn’t, and then things get messy. In the back of my mind I knew that the clock was ticking and we needed to get to a more sustainable workload without slowing down the project itself, but I personally really underestimated how quickly that transition needed to happen.

The effects of compounding also showed up in our outreach efforts. If I’d only worked on this on my own, Vaccinate NJ wouldn’t have had nearly the impact that it ended up having. Without the power of the internet to broadcast a message to the world instantly, the project wouldn’t have been possible at all. Without the systems that let the project move forward on its own without being bottlenecked on any one person’s input, we would’ve been too slow. Compounding is one of those things that gets talked about all the time these days, but there’s still little that compares to experiencing it firsthand.

Software matters

Software matters. Good software matters.

We built this entire project without any of our core team members ever meeting up in the same physical location (for obvious reasons). All of our coordination was possible because the software worked. It’s so easy to take software for granted, but it really is an unsung hero behind it all. Without software, Vaccinate NJ would’ve been impossible to pull off.

On day 0, I put a website on the internet. From day 0 onwards, the infrastructure supporting the website worked without fail. Deploying a website update was seamless, orchestrated by countless invisible electronic processes behind the scenes. Our website did not crash. Neither did any of the other software we built. Nor did the tools we used, including email, collaborative document and spreadsheet-editing software, social media, and analytics tools. The software worked, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

In addition, our ability to move fast not only had to do with the software’s reliability, but also accessibility. It was easy to get our hands on the computer programs we needed, which translated directly to speed when it mattered most. Instead of needing to waste precious time wrestling with bureaucracy and seeking grants and managing expense reports, I was able to spin up the first public version of the Vaccinate NJ website in one evening, working alone. Those software expenses were covered using yet other software that made payment possible without even requiring me to leave my room. In total, setting up the first version of the website cost less than eight dollars.

Throughout the course of the vaccine rollout, social media was a hotbed of vaccine availability discussion. Often we’d find information transmitted not from any sort of official communication but rather through ordinary word-of-mouth: someone would post a picture of a band-aid on their arm and how they got it; others might have confirmed a rumor of available appointments; still others would be busy offering transportation to and from vaccination sites, among other efforts. Throughout the pandemic, it was software that made activities like these feasible.

It was already challenging to coordinate the manufacturing and then worldwide distribution of billions of doses of a substance that literally did not exist before the pandemic started. It would’ve been immensely more difficult without software, to say nothing of all the other roles software played during the pandemic: information repository, broadcasting medium, message broker, coordination tool, video call infrastructure, lifeline to loved ones, place to vent, wellspring of comfort, cause of laughter, and– most importantly of all– source of hope.

Epilogue

Roughly half a year after Vaccinate NJ started, we decided to start winding the project down.

To be clear: this choice doesn’t mean there are no more crises, or that COVID-19 has been fully eradicated. There remain challenges when it comes to the vaccine rollout that have not yet been resolved, and managing COVID-19 remains an ongoing task. However, the challenge that Vaccinate NJ was specifically meant to solve– providing accurate, up-to-date information about appointment availability and eligibility status– is no longer the central problem in the vaccine rollout, and we believe others are better positioned to take things from here.

There are many roles that individuals and organizations play in our response to COVID-19, and we strove to do our part as best as we could. We will comfort those who are suffering, remember those who have passed, and do our best to move towards happier times on the path ahead. I’m immensely grateful for all the contributions of every volunteer who helped out, and for the opportunity to support our communities in times like these. It’s truly been an honor and a privilege.

End notes

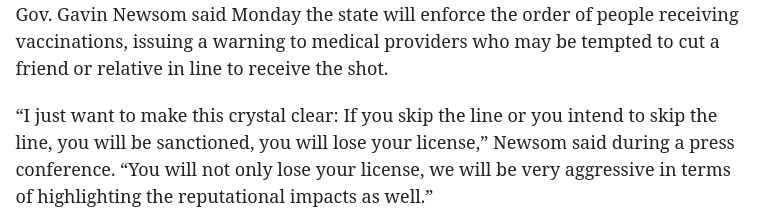

1: A note about a side effect of eligibility rules as they were originally implemented:

Vaccination sites do not operate around the clock. In addition, vaccine doses needed to be stored in special freezers and could only be used after being properly thawed out. This combination of factors meant those giving vaccines needed to be aware of vaccination site closing times so they could administer all the doses that had been thawed for the day. Any leftover doses could not be re-frozen and would expire as a result.

It was practically impossible to perfectly predict how many doses they’d need each day– even the most foolproof appointment systems often run into no-shows, cancellations, and various other unexpected events. As a result, it was quite common to have a few leftover, soon-to-expire doses and no eligible people to receive the vaccine at closing time.

You might observe that, even if there weren’t any eligible people around at closing time, there might be plenty of ineligible, not-yet-vaccinated people around. You might also observe that it would be better to vaccinate an ineligible person than to let the dose expire and throw it away.

However, eligibility regulations were particularly severe at the start of the vaccine rollout. The result was as you might expect.

New Jersey (note that the important detail about vaccine expiration is buried six paragraphs deep in the article).

2: Much has been written over the course of the pandemic about the concept of “antivax” (anti-vaccine) or “vaccine hesitancy”. It was my experience that many of these hesitations and questions were often remarkably straightforward to resolve, so long as the question-asker could trust that the answer came from another person rather than a faceless institution.

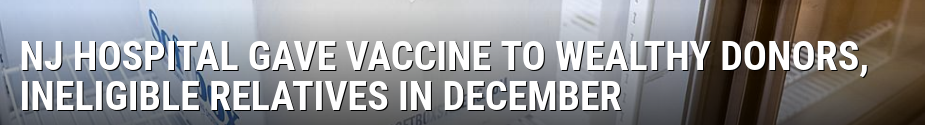

Two common questions, from here and here respectively.

I found that it helped to not immediately write people off when they expressed concerns with the vaccination rollout.

Thanks to Scott Hansen for comments/corrections/discussion.